The 150th anniversary of the Suez Canal, inaugurated on November 17, 1869, will soon be upon us.

Since its opening the Suez Canal has served not only its beneficient purpose for the transport of goods but, in a historic example of the dangers of unintended consequences, the Canal has also been the vehicle for the introduction of Red Sea organisms into the Mediterranean Sea.

Alberto Gennari

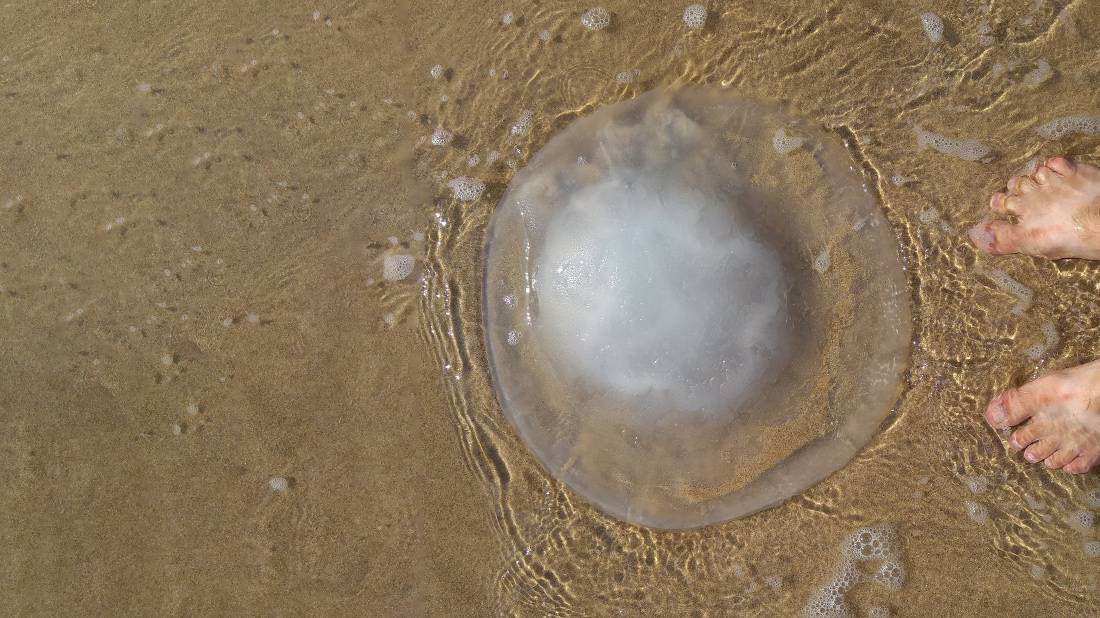

In the Israeli Mediterranean coastal ecosystems, these non-indigenous organisms present serious threats to the local biodiversity, at the very least comparable to those exerted by climate change, pollution and over-fishing. The number of Red Sea non-indigenous species, currently about 400, has more than doubled in the past 30 years. This biological invasion is causing a dramatic restructuring of biotic communities, altering ecosystem functions and affecting the availability of biological resources, ecosystem services and human health. Dense populations of the Red Sea herbivorous rabbitfish have turned native algal beds to barren grounds with a dramatic decline in habitat complexity, biodiversity and biomass; the summer swarms of nomadic jellyfish deter beach goers with their sever stings; half of the commercially important fish and nearly all crustaceans are Red Sea non-indigenous species which have displaced and replaced the native edible species.

The recent massive enlargement of the Suez Canal and an increase in temperature and salinity of Mediterranean seawater over recent decades confers advantages to Erythraean (Red Sea) newcomers, and they are more likely to colonize, establish viable populations, and spread into new habitats.