It’s hot outside, the glaciers are melting, and forests are being cut down and burned.

We hear about the climate crisis all the time, but it’s not always clear what it has to do with us.

The exhibition, “Global Warning: The Climate, the Crisis and Us”, presents the climate crisis and its effects. The exhibits in this exhibition include satellite images of open landscapes that have been impacted by the climate crisis in different ways and during different periods.

The images, which were taken from NASA’s website, are displayed in pairs: each pair displays a specific geographical region on two occasions separated by several decades, a few years or even a few days.

These images provide visual evidence of the dramatic changes experienced by the earth following climate change. Whether these are floods and fires, or invasive species flourishing to the point of impacting the ecological balance, we can already feel the results.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Europe is turning brown

Europe changes color following a heatwave: above – July 2017; below – one year later, July 2018

These two photos of the European continent were taken in July, at an interval of only one year, but the change is clear to the eye. This continent, characterized mainly by green landscapes, has turned brown. According to the European Space Agency, this change took place within just one month!

The first part of the summer (1 June to 16 July) brought on a series of heatwaves. Countries such as Germany and Britain experienced record-breaking temperatures and even drought conditions. All of these led to dehydration and a change to the familiar green European landscape. Beyond the beautiful landscape pictures that you won’t be able to take on your next trip, the significance of this change is, among other things, an increase in the amount of dry material, which might cause fires breaking out in the region to become wildfires. Such fires not only cause significant damage, but also emit copious quantities of carbon dioxide, the same greenhouse gas whose increasing atmospheric concentration causes global warming. Look for the videos taken with a carbon dioxide camera, displayed on the exhibition’s entrance screen; there you’ll see with your own eyes the greenhouse gases emitted during burning. Thus we have a vicious circle: climate change increases the severity of the fires, which emit high quantities of carbon dioxide, thus exacerbating the climate crisis. This circle must be broken. Suggestions for actions that you yourselves can do may be found in the exhibit “Your Move” in the exhibition.

Death of a Glacier

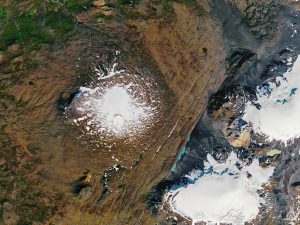

A glacier in Iceland in the last stages of its disappearance: above – September 1986, below – August 2019

The glacier, Okjökull, in western Iceland, is gradually disappearing. The glacier’s name combines the name of the volcano on which it is located – Ok – and the Icelandic word for glacier – jökull. A geological map from 1901 showed that the glacier once covered an area of approximately 38 square kilometers. Aerial photographs from 1978 showed that the glacier had shrunk to 3 square kilometers. Currently, less than one square kilometer remains! For the sake of comparison, the glacier’s area was once equivalent to the combined area of Herzliya and Ra’anana; its present area is equivalent to the area covered by our museum exhibitions.

The Okjökull glacier was declared dead in 2014. A dead glacier is a glacier that has stopped moving. The slow movement of glaciers is what creates the beautiful frozen landscape patterns familiar to us. In 2019, two researchers held a memorial ceremony for the glacier, and later on a headstone was erected in its memory. The following text was written on the headstone:

A letter to the future

Ok was the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier.

In the next 200 years all of our glaciers are expected to follow the same path.

This monument is to acknowledge that we know

what is happening and what needs to be done.

Only you know if we did it.

What are the potential impacts of glacial disappearance?

The glacial area has a direct impact on temperature. If you have (or had) a vehicle, you will surely know that in a perpetually warm country like Israel, a light-colored vehicle is preferred. Light colors, particularly white, reflect the sun’s rays. A white surface, such as a glacier, heats up less than surfaces of other color. Dark substances absorb solar radiation, and thus heat up much more. Glacial melting increases the earth’s dark surface area (oceans), leading to greater absorbance of solar energy and an increased rate of warming. You can try this out yourself: look for the “On Thin Ice” exhibit, measure the temperature of the ice surface and compared it with the temperature of the ocean surface.

Warming up the beatles

Damage caused by bark beetles to pine trees in South Dakota: above – October 1992, below – September 2018

The pine forests of South Dakota have been damaged by a combination of two factors, both resulting from climate change. In the photos you can see the effects of the damage caused by the bark beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae, to the pine trees. The beetle’s scientific name means “large tree destroyer” – a name that speaks for itself. These beetles lay their eggs under the tree’s bark, and the larvae hatching from the eggs feed on the tree. The beetle also injects a fungus into the tree that weakens it and decreases its ability to prevent beetle penetration. These two factors lead to the death of the infected tree, since they damage the tree’s vascular system (xylem and phloem) and block the supply of water and food to the different parts of the tree. About a year after the tree is infected by the beetle, its needles turn red. Such a tree is considered to be dying, or dead.

How is this connected to the climate crisis? Usually, the cold weather prevailing during winter kills some of the beetles’ eggs and prevents the population from proliferating, but recent winters have been warmer than usual, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of beetles. At the same time, prolonged dry conditions have weakened the pine trees and increased their vulnerability. The combination of these climate variables has caused the damage to the pine population.

But the damage doesn’t stop there. Life in nature is a web; disruption of the balance in one part triggers a chain of events. We humans are also part of this web. Our daily activities have the ability to affect the climate crisis. Will it be for good or for bad? Such decisions depend on each and every one of us.

Let’s become part of the change for good. It begins with us in the exhibition Global Warning: The Climate, the Crisis and Us.